The recent play of Muck & Brass has been occupying my sleeping nights and bedraggled shower time. I’ve no great conclusions other than that 5-days-for-everyone is a Bad Idea (see below). The rest is just terrain mapping.

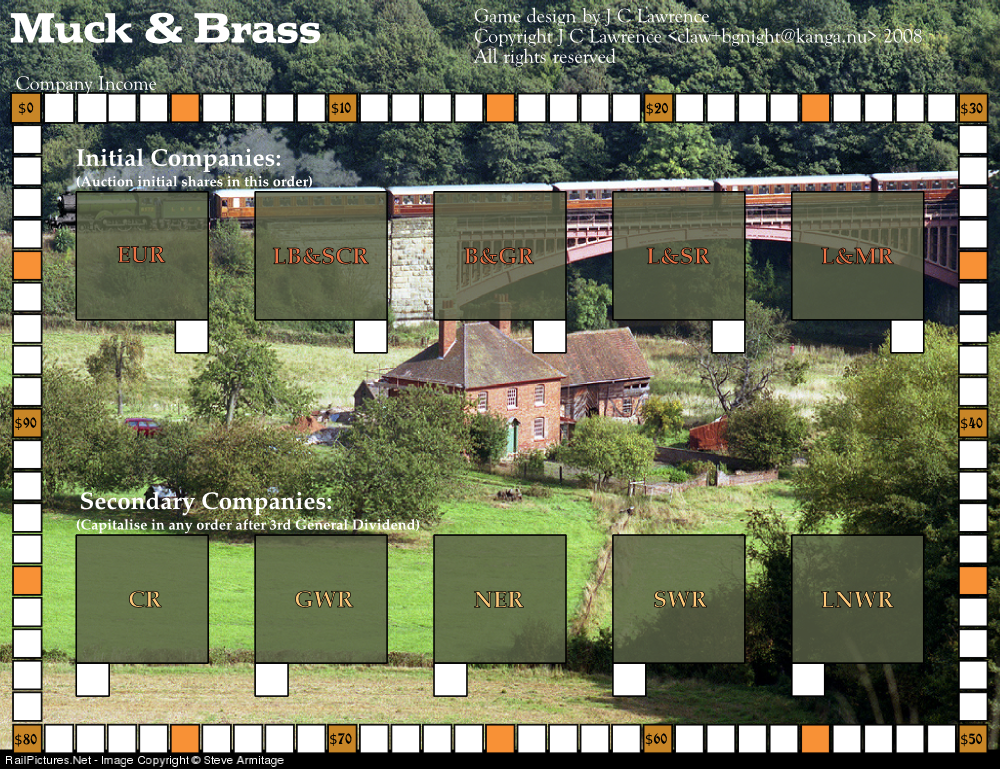

The standard action pattern in the recent game was a spate of Expands followed by a mix of Develops and Capitalises. Typically the final actions were chosen to either force the round closed, or to put the next player in a position to force the round closed. The only times Capitalise was selected early was when either all of a player’s companies were broke or in the late game in order to float more secondary companies in order to extend game length (it was set to end in the sixth General Dividend with only two companies left operating but we called the game early mid the 5th round due to other constraints).

Unlike Wabash Cannonball early capitalisations were not seen as critical early moves, in part due to the high opportunity cost of the Capitalise action (time), but also because there are simply so many shares available (10 unsold shares) and relatively little to differentiate among them. The result is that Muck & Brass is mostly not about temporary emergent alliances but about the old standards of arbitrage, opportunity and tactical position.

In a four player game the dance is straightforward:

- Stay low/early in the turn order to get more Expands for your companies

- Buy lots of shares (difficult when you’re low in the turn order)

- Buy shares that players lower than you in the turn order also have so that you profit from their activities

- Try to keep your own shares undiluted

The lack of a Chicago-style golden target to create a discontinuous value set is the main characteristic that precludes temporary emergent alliances. What alliances there are, are happenstance collisions of mutual interest rather than deliberately managed affairs. As such the player relationships are much closer to Preußische Ostbahn’s management of temptation and exploitation than Wabash Cannonball’s forthrightly collusive work-together-and-we-both-make-more.

In our game, because of the high opportunity cost for capitalisation, Capitalise was usually used as a round ender to re-invigorate a cash-less company or to setup turn order for the next round. Thus the first round looked something like:

- (E7/D5/C3)

- P1-E2/2 P2/E2/2 P3-E2/2 P4-D1/2 P4-E2/2 (E3/D5/C3)

- P1-E2/4 P2-E2/4 P3-E2/4 P4-C3/5 (E0/D5/C2)

- P1-C3/7 P2-C3/7 (E0/D5/C0)

The second round was a little more interesting as London started to be developed, thus freeing up a host of other possible Develops for other companies:

- (E7/D5/C3)

- P1-E2/2 P2/E2/2 P3-E2/2 P4-D1/2 P4-D1/1 P4-E2/3 (E3/D4/C3)

- P1-E2/4 P2-E2/4 P3-E2/4 P4-C3/6 (E0/D4/C2)

- P1-D1/5 P2-D1/5 P3-C3/7 (E0/D2/C1)

- P1-P1-D1/6 P2-D1/6 (E0/D0/C1)

The third round was similar, but with even less Capitalisation:

- (E7/D5/C3)

- P1-E2/2 P2/E2/2 P3-E2/2 P4-D1/2 P4-D1/1 P4-E2/3 (E3/D4/C3)

- P1-E2/4 P2-E2/4 P3-D1/3 (E0/D3/C3)

- P3-E2/5 P4-C3/6 (E0/D3/C2)

- P1-D1/5 P2-D1/5 (E0/D1/C2)

- P1-D1/6 (E0/D0/C2)

Such a lower rate of capitalisation encourages companies to run with broke treasuries, for positions to be more heavily invested, and for strong player differentiation, both positional and financial (low cash high income versus lower income and high cash). It also encourages players to forgo Capitalise and instead Develop heavily as it has similar effects on income (and slows the game down). From a design perspective these are all desirable patterns, not least the slowing of the game.

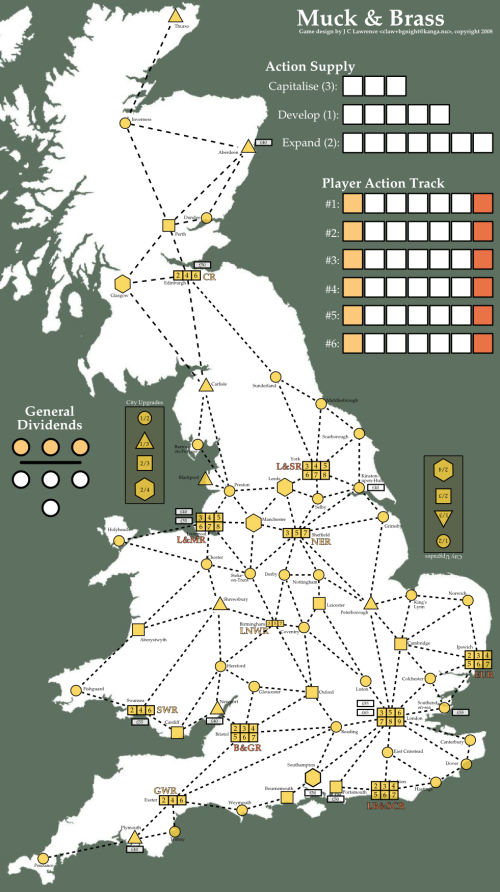

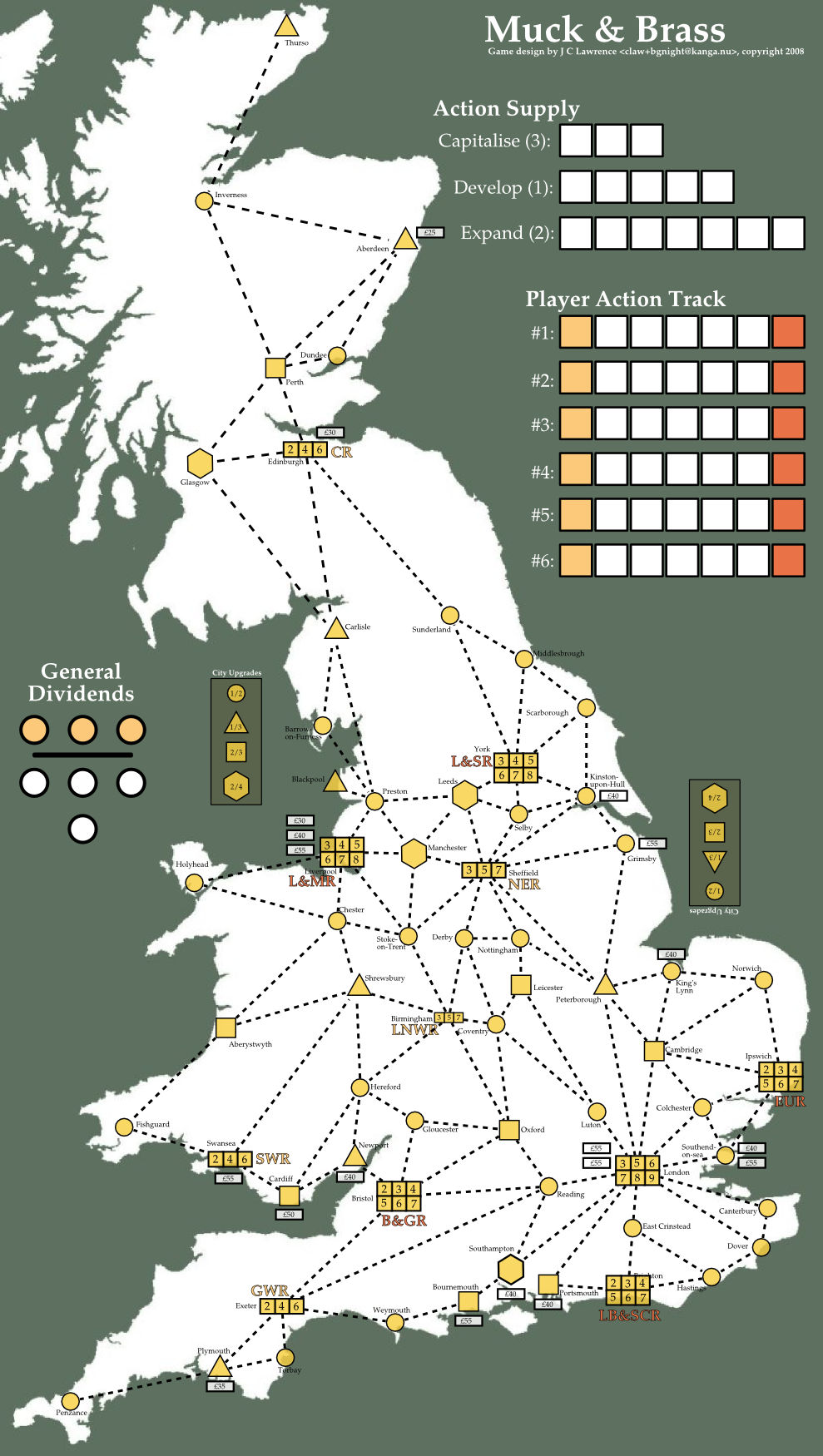

The players clearly valued Expand higher than the other actions. I’m not convinced they were wrong. Getting to London is critical for most companies and building out of London not only offers a larger income delta than any other activity (once London been developed once), but also positions for ready mergers with the three companies surrounding London. In our game the B&GR built 5 connections out of London. When London was developed up to $9, that was $45 income for the B&GR: $14/share just for London alone!

Consider a hypothetical 4th round of a game:

- (E7/D5/C3)

- P1-E2/2 (port/merger) P1-C3/5 P2-E2/2 (port/merger) P2-C3/5 P3-E2/2 P4-E2/2 (E3/D5/C3)

- P3-E2/4 P4-D1/3 (E2/D4/C3)

- P4-D1/4 (E2/D3/C3)

- P3-E2/6 (float or merger) P3-C3/9 P4-E2/6 (float/merger) P4-C3/9 (E0/D3/C3)

- General Dividend (two players past 6 days)

Four secondary shares were sold. There is potentially only one company left in the mix. The game could have just ended. Or, more likely there are less ports and mergers as there’s just not enough money in the other companies/players for the Expands required for ports and mergers. The players early in turn order are likely to have shares in companies with cash for ports and mergers:

- (E7/D5/C3)

- P1-E2/2 (port/merger) P1-C3/5 P2-E2/2 (port/merger) P2-C3/5 P3-E2/2 P4-E2/2 (E3/D5/C3)

- P3-D1/3 P4-E2/4 (E2/D4/C3)

- P3-D1/4 (E2/D3/C3)

- P3-D1/5 P4-D1/5 (E2/D1/C3)

- P3-D1/6 P4-C3/8 (E1/D0/C2)

Two secondary shares just sold and one arbitrary share was capitalised. Assuming that mergers were done instead of port builds there could be as few as 3 companies left in the game. Assuming instead that P4 had a share of a company that could merge with a single expand the last actions set could have been:

- P3-D1/6 P4-E2/7 (merge) P4-C3/10 (E0/D0/C3)

In which case there could potentially be only two companies and the game would be over depending on what share P4 force capitalised. P4 has three choices:

- Capitalise the first share of any secondary company. This clearly makes sense if P4 will win as the game ends

- Capitalise the second share of a secondary company which is already connected to a company in which P4 is invested. This assumes that one of the earlier players capitalised the first share of that company. In practice this usually means either the NER, LNWR or GWR and only makes sense (again) if P4 is will win as the game ends

- Capitalise the second share of an unconnected company. This will put three companies back in the game causing the game to not (yet) end.

The choice-set is interesting because P1 and P2 control whether #2 is even present as a choice, and which company fits #3 (likely one near their investments). Neat!

More immediately useful is that without the forced 3 days for the merger there’s a reasonable potential for a merger storm in the fourth round that instantly ends the game. The real problem is that it is absurdly difficult to control or predict the values generated by such a merger storm from the preceding rounds making the game results essentially a crap-shoot. Scratch that idea!

The other perspective is that ports effectively offer several values to minor investors:

- Cause a special dividend

- Impoverish a company such that it can’t afford to drive future mergers

- Ability to capitalise a share that encourages a merger-via-Capitalisation along with its related Special Dividend (ie a connected secondary company)

Mergers deliver all the above plus the following:

- Accelerates game-end condition

- Builds a combined treasuring which is likely large enough to afford another merger or port

Mergers are generally better for major investors as they provide two forums for special dividends for their heavily invested shares. Ports conversely offer only one future venue for additional secondary dividends but protect other investment’s special dividend capacity from predation by a steamrollering behemoth.

The other advantage for forced 3 day capitalisations is that players are now encouraged to capitalise more heavily in the early rounds in order to get enough cash into their companies to afford special dividends be they from ports or mergers. However this early capitalisation rush exposes another phantom that pushes back on such heavily capitalisation. Imagine the following perhaps not-quite-so-fantastic evolution:

- P1 is invested in the L&MR (possibly even a minor investor), Expands to a port in Liverpool and force-capitalises the NER

- P2 is invested in the L&SR (possibly also minor), can’t afford a nearby port and so merges with the EUR or LB&SCR for a special dividend. P2 then force-capitalises the NER to make a L&MR/L&SR/EUR/NER merger for yet another special dividend.

- P3 is desperately behind and merges the LB&SCR or EUR into the new huge agglomerate, thereby removing the merger possibility from the agglomerate and securing their share’s dividends. P3 Capitalises something. Anything.

- P4 has a potentially remarkably ugly decision as there are only two companies left in the game, the huge agglomerate and the B&GR.

That’s two actions spent for 3 special dividends. Oof. What’s different is that huge gobs of money have just been thrown into the mix by the three mergers. P4 is really wishing he owned a good spread of the northern companies at this point. Double oof.