Reaching the Third Rail

A little more playable:

A little more playable:

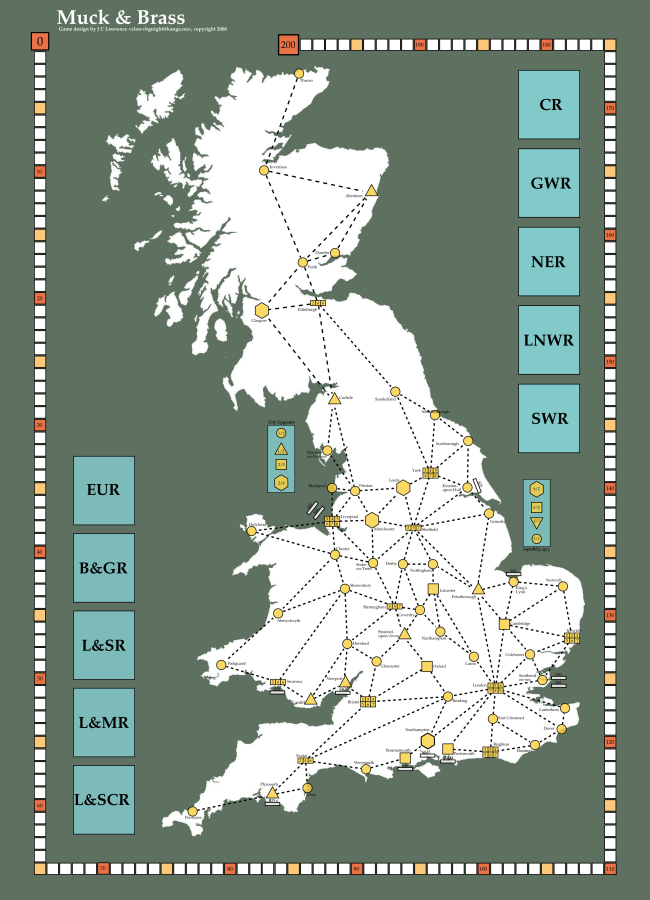

Previously I’ve had trouble drawing a score track that I thought reasonable. Some of it was as simple as how to get a nice looking score track with highlights every 5 and 10. Then there are more complex items such as how to get a rectangle that loops at exactly 100? 200? I’ve been asked this more than once and it really isn’t that hard.

A few small blindingly obvious (in retrospect) tricks work wonders:

A little arithmetic will yield how long your sides will need to be for a closed loop of 100 or whatever. Just chop your horizontal to that length, do the align bit, chop the vertical to suit, make the U-shape, copy up another horizontal row, align it again to the corners and Bob’s your uncle yet again.

Quite a few changes this week.

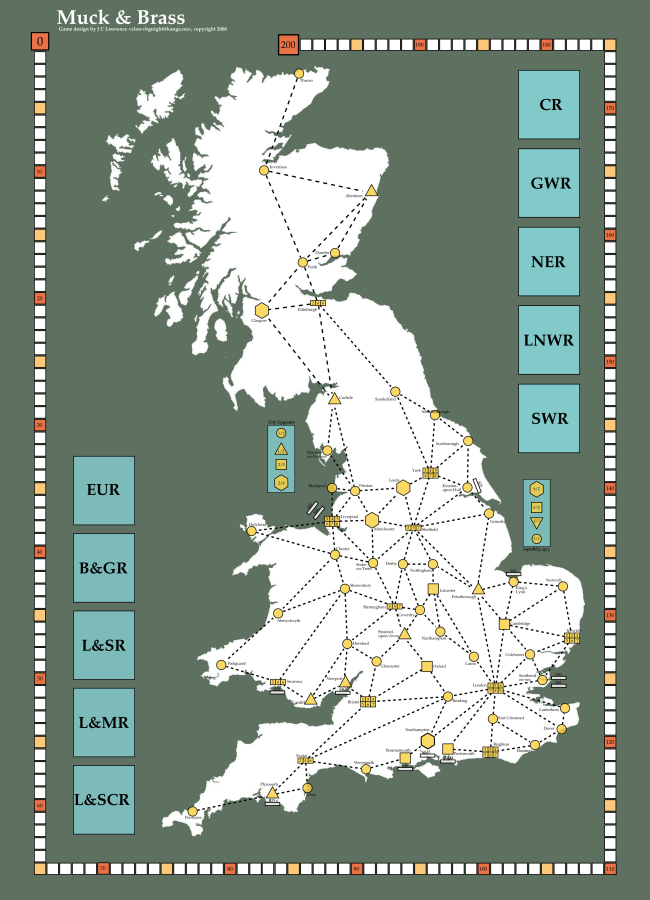

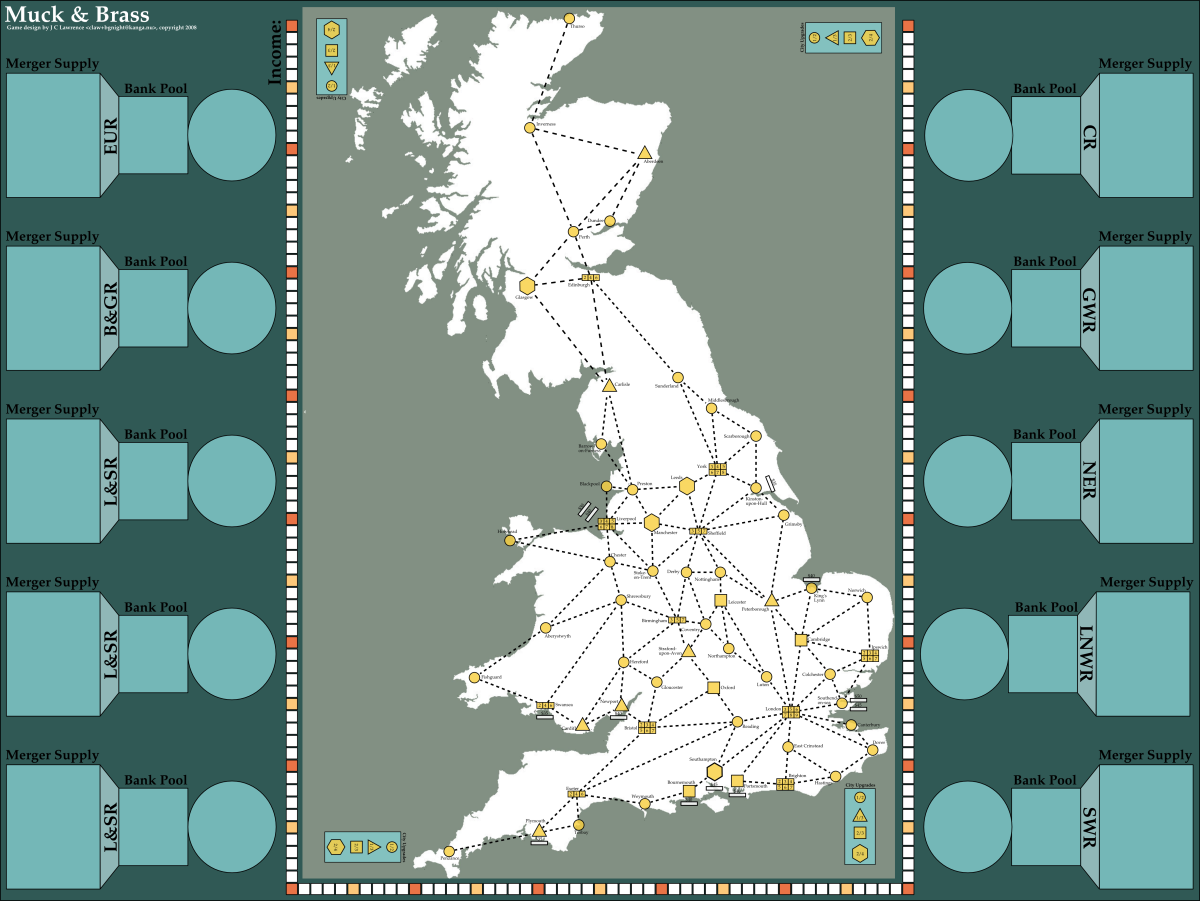

I spent a few hours digging through the early history of the English railways from around 1830 onward and picked a more representative set of companies for the areas I’ll be putting them in. I also ordered them by starting date so that the initial companies did in fact start earlier as railway companies and the merger companies did in fact start later and heavily focused on mergers (eg GWR, LNWR, NER etc). There are a large number of goofs in home stations, but none I hope egregiously large (eg the GWR starting in Exeter?).

The current initial companies are:

Merger companies:

I’ve also had a first pass at allocating share counts for the initial and merger companies. Total gut sense with initial companies running from 3-5 shares and merger companies running 8-10 shares. I’m clearly going to have to play with those numbers.

The rules are looking pretty clean now. Not final but at least playable without instant gamer-pattern baldness.

A remaining problem is what order to auction the initial company shares in? It is tempting to do them in historical opening order which would be: L&MR, L&SR, B&GR, EUR, and finally LB&SCR. I’m not so happy about the very ordered progression from north-to-south that sequence represents on the map – despite the fact that the industrial furnaces of the midlands did actually drive the industrial and railway revolution in England. My sense is that the auction ordering should pose immediate spending challenges with early risks made in spite of later temptations. The three companies near London are obviously attractive – London develops beautifully and there are many fine ports to the south (the white bars) which offer Special Dividends – but having them come together as a group seems…wrong/odd. Likewise for the L&MR and L&SR with the wonders of Sheffield, Leeds and Manchester right next door. Urk.

Proposal:

Of course that’s all higgledy-piggledy for historical dates, but it may work better. I’ll have to sleep on it.

Over the last couple days I moved the map from yEd over to Inkscape and into SVG format. Unfortunately this required a nearly from-scratch redraw as I lost patience writing the script to post-process yEd’s concept of what it should produce for SVG elements versus what I thought I wanted. Fortunately for such a simple graph this did not take long. A few colours here and there, an income track, yada yada and voial!

Note to self: Must remember to put numbers on the income track.

The bit about the active player choosing which side of the merger pays the Special Dividend could be a doozey. It allows minor shareholders with similar holdings to collude across turn order in order to cause mergers which mutually benefit them but not necessarily the plurality shareholder. Consider:

PlayerX owns a significant plurality of CompanyQ. PlayerY and PlayerZ both own but a single share in CompanyQ. CompanyQ is two single builds away from merging with CompanyR. Both PlayerY and PlayerZ have significant holdings in CompanyR. CompanyR is too far from CompanyQ’s home station to consider the merge that way. So, PlayerY builds one of the links toward CompanyR and PlayerZ builds the second and as predicted by PlayerY, selects CompanyR for the Special Dividend. PlayerX with no investment in CompanyR is of course overjoyed to be shut out of the Special Dividend. PlayerX would have far preferred to build the connection himself and declare CompanyQ for the special dividend but was outflanked by the emergent collusion among PlayerY and PLayerZ.

Other forms of possible insurrection and insurgency by minor share-holders abound. I’m not clear if this is delightful or merely fatal yet. In terms of layering the incentive mesh formed by share-ownership however, this is quite delightful.

The new more historically flavoured merger rules read as follows:

When a company connects to another active company’s home station the two companies merge. A merged company may have several home stations from its constituent component companies. The active player decides which of the two companies will be acquire merge into the other acquiring company.

The acquired company pays a Special Dividend (see Dividends)

Any unbuilt track markers for the acquired company are added to the acquiring company’s supply

Each player’s shares in the acquired company are replaced 1:1 with shares from the new parent company. Shares are initially taken from the bank pool of the acquiring company, then shares from the merger supply for that company. The shares of the acquired company are placed face-down in the bank pool of the acquiring company so that it may be clearly seen that it is now a component-company.

The income of the acquired company’s income is added to the acquiring company’s income, and the acquired company’s marker is removed from the income track

After the merger is resolved the active player selects an inactive merger company to start. If the new merger company’s home station is already connected by track, the connected companies will be acquired by the new merger company.

Any unbuilt track markers for companies that have connected track of the home station of the new merger company are added to the merger company’s supply

Each player’s shares in the companies that have connected track to the home station of the merger company are replaced 1:1 with shares from the new merger company. Shares are initially taken from the bank pool of the merger company, then shares from the merger supply. The shares of any acquired companies are placed face-down in the bank pool of the merger company so that it may be clearly seen that they are now component-companies

A share of merger company is auctioned in the normal manner (see Capitalise). The new share is taken from the merger company’s merger supply if a share is not available from the bank pool

If the merger company’s home station is already connected by track, the merger company pays a Special Dividend (see Dividends)

The winner of the newly auctioned share selects the next merger company to start, starting the merger process all over again

If no players bid on a merger auction the auctioning player discards the share into the bank pool and receives the current income of the company divided by the current number of issued shares including the just auctioned share in exchange.

If all the merger companies have been started and a merger occurs, the active player may either pass on the rest of their turn, or may auction any available share from the bank pool in the normal manner (see Capitalise).

Quite a bit cleaner. Conversations with Ben Keightley (Coca Lite) have caused me to re-examine this simplified model, though I don’t think that was his intention. In particular I’m re-considering the automatic chaining of mergers. I’m not sure it is justified. Without automatic chaining the mergers will still tend to happen in a flurry, that is where the money is, but it will not be quite as uncontrollable an orgy and allows for interesting decisions to be made between mergers (eg track blocking) which are not possible with automatic chaining. The specific relationship of turn order and share investments also becomes more interesting. In short methinks I’ll lose the automatic chaining of mergers. I see little loss and much potential game.

The other change, and this is a biggie, is allowing the active player to determine which of the sides of a merger will pay the Special Dividend. This change was done on a whim but it feels right. It allows minor share-holders to merge foreign companies into a company in which they hold more stock, thus getting the Special Dividend where they want it while also building the agglomerate.

The current merger rules for pre-connected home stations (see below) are backwards. The merger companies were the agglomerates. The GWR (for instance) was a merger of many other smaller railway companies, as was the LNWR the NER, etc. They also (obviously) started later than the companies they acquired.

Thus, I’m reversing the direction of share flow for mergers. If a merger company’s home station is connected when it starts, all the connected railways merge into the merger company (which makes a sort of historical sense), and then the merger company pays out a special dividend. Of course this makes no difference in terms of where the money goes and how much of it, but it does make better thematic and historical sense. It also makes the game slightly cheaper to produce as less merger shares will be needed for the initial companies.

Good progress today. I’ve finally a full working draft of the rules, complete with all companies (initially) historically researched and specified, and the text for the actions even makes some sense.

Next is polishing and bringing the map up to date followed by a good bit of number crunching simulation and analysis. Ah, the joys of abstract game design. But for now it is time to go off and watch some Anime. Blue Seed, Junkers Come Here or Voices of a Distant Star?

A working concept for mergers:

When a company connects to another active company’s home station the two companies merge. A merged company may have several home stations. The company that built the track will be acquired and will merge into the other company.

The acquired company pays a Special Dividend (see Dividends)

Each player’s shares in the acquired company are replaced 1:1 with shares from the new parent company. Shares are initially taken from the bank pool of the acquiring company, then shares from the merger supply for that company

The acquired company’s income is added to the acquiring company’s income, and the acquired company’s marker is removed from the income track

Any unbuilt track markers for the acquired company are added to the acquiring company’s supply

After the merger is resolved the active player selects an inactive minor company to start. The new minor company’s home station will either still be unconnected or be connected by track from one or more companies.

Starting a minor company whose home station is unconnected by track:

Starting a minor company whose home station is connected by track:

The winner of the newly auctioned share selects the next minor company to start, starting the merger process all over again

More than one company has built a connection to the home station of the new minor company, then connected companies are auto-merged and the new minor company is considered to be auto-merged into that parent company:

The active player selects one of the connected merging companies to be the new parent. Each player’s shares in the acquired company/companies are replaced 1:1 with shares of the new parent company. Shares are initially taken from the bank pool for the acquiring company, then shares from the merger supply for that company

If no players bid on a merger auction the auctioning player discards the share into the bank pool and receives the current income of the company divided by the current number of issued shares including the just auctioned share in exchange.

While the wording will undoubtedly be tightened, hopefully it at least makes (non)sense. Without adding a host of special rules about building into secondary company’s home stations, which seemed needlessly complex, this was the simplest pattern which combined player-predictability, (relative) simplicity and (reasonable) transparency while also offering potentially interesting game decisions — especially once they start to chain.

The following escape hatch to the share auction is attractive:

If a player auctions one of their own shares and no players bid, the player may put the share back into the bank pool and receive the current income of the company divided by the current number of issued shares including the just auctioned share in exchange.

What a delightfully nasty and abusive money pump, especially in lower player count games! I fear my auction theory is too weak to predict out all the implications. I should probably spend some time talking it over with with the auction theory guys at Stanford before committing, but I sure like the idea so far.

Below is a possible introduction section for the rules. Some of the stated goals, like the duration, may be ambitious, but that’s the nature of good goals:

After the birthplace of the steam engine, railway development in England was a rocky and tortuous affair. Bankruptcies were common. Struggling railway companies merged and then merged again, acquired other companies and became not-so-vast agglomerates. In Muck & Brass players will invest in railway companies and then attempt to leverage their investments for profit. Railway companies will start, grow and then merge into each other as yet more companies pop up to join the frenzy of growth and mergers.

During the course of the game players will buy and sell dividend-paying shares at auction, build track to increase the income of the companies they own shares in, and develop the industrial base of cities the companies serve to further increase their income. After a period of heady growth companies will begin to merge, creating both ever larger income vehicles and prompting new companies to join the growth and merger fray.

By carefully controlling and timing the purchase and sale of shares, the railway networks their companies build, the development of the cities they connect and the mergers of the companies, players may leverage their investments for great profit.

The game ends after one or more of:

the seventh (7th) general dividend

only two operating companies have unsold shares

only two operating companies have a legal track build and can afford it

The player with the highest net worth at the end of the game wins.

Muck & Brass supports 3 through 6 players, is particularly recommended for 4 or 5 players and plays in around 90 minutes.